Se ha instalado en el último tiempo, tanto en la academia como en la opinión pública, la idea de que liberales y republicanos pertenecerían a tradiciones antagónicas; los primeros, poniendo el énfasis en el individuo y el crecimiento económico, los segundos en la comunidad y el bien común. Paradójicamente, quienes exponen dicha división taxativa provienen tanto de la izquierda como de sectores conservadores de derecha para quienes el liberalismo promueve un individualismo exacerbado. Permítaseme plantear algunas dudas al respecto, las cuales son tanto de carácter histórico como interpretativo.

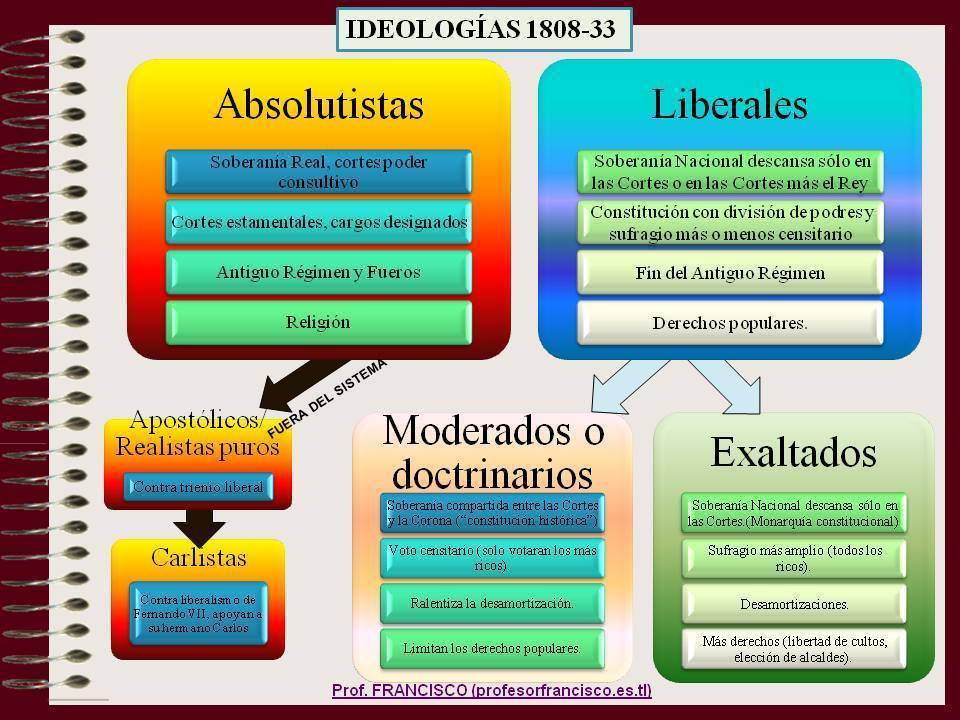

En primer lugar, quien crea que el liberalismo es una corriente unívoca y monolítica comete un profundo error históricoconceptual. Los orígenes de la palabra “liberal” se retrotraen a las Cortes de Cádiz (18101812), un lugar de discusión política donde diferentes sectores respaldaron posiciones liberales más o menos individualistas, más o menos estatistas. En efecto, hay tantos liberales “individualistas” (lo que la literatura especializada conoce como liberales “clásicos”), como liberales “comunitaristas” (o “afrancesados”). Ambas corrientes defienden proyectos distintos (unos consideran que la intervención del Estado no debe pasar a llevar la voluntad de los individuos, los otros ven al Estado como el garante de los derechos individuales), pero las dos se autoconciben como “liberales”.

Estos liberalismos decimonónicos surgieron en contextos monárquicos, pero con el paso del tiempo, los liberales —de cualquier signo— tendieron a preferir la república como sistema de gobierno. Ello quiere decir que liberales y republicanos comparten mucho más de lo que hoy se cree. Por de pronto, ambas tradiciones defienden la igualdad ante la ley y la inexistencia de privilegios. Además, las dos proponen limitar el poder en caso de que éste se concentre en una persona o grupo. Finalmente, liberales y republicanos abogan por la separación y el equilibrio de los poderes del Estado, al tiempo que ponen a la nación como la depositaria de la soberanía política.

¿Por qué, entonces, se insiste tanto en las supuestas diferencias entre liberales y republicanos? Me parece que la respuesta hay que buscarla en la asimilación causal y algo sesgada que los comunitaristas hacen entre liberalismo “clásico” y “neoliberalismo”. Si tuviéramos que resumir el “neoliberalismo” como un modelo económico en el que el Estado cumple un rol mínimo, entonces deberíamos concluir que liberales “clásicos” como Adam Smith —quien sostenía que el Estado debía jugar un papel relevante en la educación inicial— tendrían poco de “neoliberal”. Isaiah Berlin, por nombrar otro caso, terminó sus días como socialdemócrata; y, sin embargo, nadie podría poner en duda sus credenciales de liberal “clásico”. Estos dos casos —hay muchos más— comprueban que eso que los comunitaristas llaman “bien común” está también en la base del liberalismo “clásico”. Por mucho que les pese a los autodenominados republicanos de izquierda y de derecha.

Liberals and Republicans

In recent times, both in academia and in public opinion, the idea has been installed that liberals and republicans belong to antagonistic traditions, the former emphasizing the individual and economic growth, the latter the community and the common good. Paradoxically, those who put forward such a taxing division come both from the left and from right-wing conservative sectors for whom liberalism promotes an exacerbated individualism. Allow me to raise some doubts in this regard, which are both historical and interpretative in nature.

In the first place, whoever believes that liberalism is a univocal and monolithic current is making a profound historical-conceptual error. The origins of the word «liberal» go back to the Cortes de Cadiz (18101812), a place of political discussion where different sectors supported more or less individualistic, more or less statist liberal positions. In fact, there are as many «individualist» liberals (what the specialized literature calls «classical» liberals) as there are «communitarian» (or «Frenchified») liberals. Both currents defend different projects (some consider that the intervention of the State should not go beyond the will of individuals, the others see the State as the guarantor of individual rights), but both see themselves as «liberal».

These nineteenth-century liberalisms emerged in monarchical contexts, but as time went by, liberals -of whatever sign- tended to prefer the republic as a system of government. This means that liberals and republicans share much more in common than is generally believed today. For one thing, both traditions defend equality before the law and the non-existence of privileges. In addition, both propose limiting power if it is concentrated in one person or group. Finally, liberals and republicans advocate the separation and balance of state powers, while placing the nation as the repository of political sovereignty.

Why, then, is there so much insistence on the supposed differences between liberals and republicans? It seems to me that the answer must be sought in the causal and somewhat biased assimilation that communitarians make between «classical» liberalism and «neoliberalism». If we were to summarize «neoliberalism» as an economic model in which the state plays a minimal role, then we would have to conclude that «classical» liberals such as Adam Smith -who argued that the state should play a relevant role in initial education- would have little «neoliberal» in them. Isaiah Berlin, to name another case, ended his days as a social democrat; and yet no one would question his «classical» liberal credentials. These two cases – there are many more – prove that what communitarians call «common good» is also at the basis of «classical» liberalism. As much as it may bother the self-styled republicans of the left and of the right.